As an archipelago of 17,508 islands, located at a strategic position on major trade routes and possessing a rich variety of natural resources

[1], Indonesia could have great potential in a capitalist world. Still, it is one of the target countries of the UN Development Goals (UNDP). The islands of Indonesia have experienced centuries of Dutch colonization. ‘Have been dominated by’ would perhaps be a better phrasing, because the development of Indonesia has been influenced greatly by the Dutch (Geertz, 1963: 47). One could argue that the current economic state of the country is entirely due to colonization and associated exploitation and violence, but given the efforts that have been made since 1945 to alleviate poverty and boost the economy, this is not a very likely hypothesis. Instead, a significant role should also be attributed to international confidence in the country. An analysis of the post-war national economy of Indonesia shows that growth rates fluctuate with foreign investment.

Starting with a historical introduction to the Indonesian economy, this article contrasts past foreign dominance to the current independent Indonesian economy. It examines in particular the latter’s current perception by international economic parties, mainly foreign investors. Indonesia’s position in the globalizing world economy is a relevant example of how national and international trends influence each other, and together determine the path that the economy of a development country will follow.

Colonization by the Dutch started shortly after 1600. The Dutch settled mainly on Java, where the company chose as its ‘headquarters’ the city of Batavia (the current Jakarta).

[2] From this period onwards, Java was to be the center of Indonesian development. Jakarta, currently the capital city of Indonesia, is still the economic center of the country, and deep contrasts exist between the latter and the country side, which is more often than not characterized by extreme poverty.

On other islands, the Dutch initiated cultivation of former rainforest, in order to export goods like nutmeg, coffee, pepper and sugar. Because of Dutch interference, the original trade with continental Asia was paralyzed and villages were no longer self-sustainable. The infrastructural orientation changed profoundly. Village production was taken to the main export centers like Batavia, instead of being exported to continental Asian countries, as was done before the Dutch arrived. In and between these colonial centers (mostly located on Java), ports, road systems and railways were developed. Because of their ‘core’ function (politically and economically), capital accumulation occurred mainly here.

The main export industries were established during the 19th century. There was now more direct involvement of the Dutch in the Indonesian agriculture, including Dutch settlement and exploitation, mainly as resource depletion. This was linked, first, to the Cultivation System

[3], which also resulted in more large scale land cultivation and massive migrations to Java, and later to Dutch traders leasing Indonesian land.

[4] On the East-coast of Sumatra, plantation economy arose. (Britannica)

The main industrialization took place on Sumatra and Java, due to the relative wealth of, and the amount of Westerners on, these islands. Very influential were the new agricultural technologies that were introduced in this period. This enabled rubber and petroleum production and exports to rise during the early twentieth century (Library of Congress Country Studies, 1992). Mainly on Java and Sumatra, irrigation systems were introduced to flood the rice sawas.

Decolonization started in 1945, when Indonesia declared itself independent. Four years of severe violence followed, which were, of course, far from beneficial to the country’s overall well being.

[5] Sumatran exports only recovered in 1965 to pre-war levels (Airries, 1991: 5). In the second half of the twentieth century, heavy population growth occurred and urbanization figures (mainly in Jakarta) exploded (figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Urbanization in Indonesia. Adapted from UN World urbanization prospects (2005)

Figure 1. Urbanization in Indonesia. Adapted from UN World urbanization prospects (2005)  Figure 2. Urbanization: Jakarta. Adapted from UN World urbanization prospects (2005)

Figure 2. Urbanization: Jakarta. Adapted from UN World urbanization prospects (2005)Industry and agriculture were somewhat diversified. Garment became a major export category under Sukarno (Antlov. 1997, 1172), further shifting land use and the orientation of labor from agriculture to basic industry. The dominant picture since this period is one of small scale villages exercising handicraft on the countryside, while more and more administrative occupations were located on Java. These developments led to an even more clear-cut division between a ‘core’ region (centred around Java), and a peripheral region.

Globalization and the emergence of the tourist sector were mainly influential in the core, where much more capital was located than in the outer regions, enabling more investment in trade, tourism, industrialization and infrastructure. There is still great inequality between the ‘core’ and ‘peripheral’ regions in infrastructure and economic growth.

Clearly, the legacy of colonization has been far from positive. But what happened after 1945? Why has the economic potential of the fourth largest country in the world still not been realized? The lack of economic growth and the ‘underdevelopment’ of Indonesia are often mentioned as a result of integration in the world economy. As stated by Barro, however, until the Asian crisis of 1997, there was rapid economic growth in Indonesia:

“Before the 1997 financial crisis, the fast-growing economies of East Asia were favorites of economists and international investors. Then Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, and Thailand were hit hard with currency devaluations and high interest rates. A 40-year period of sustained rapid growth was replaced in 1998 by sharp economic contractions in these countries, ranging from 7% in South Korea to 15% in Indonesia.” (Barro, 2001: 1)

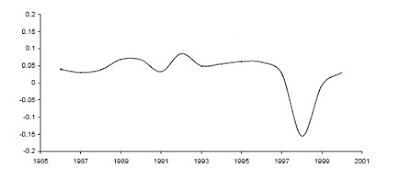

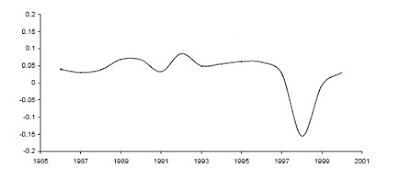

Also, in the 1970s, plantations’ exports rose from 445,611 tons to 951,985 tons (PBS 1985, 100), a more than 100% growth. Between 1965 and 1990, Indonesia’s rate of economic growth was twice as high as the World Bank figures for the Middle Income group of countries (Hill, 1994: 833). In fact, as can be seen in figure 4, it was the 1997 crisis that changed the economic situation, not only of Indonesia, but of the ASEAN countries in general.

Figure 4. Per capita GDP growth in Indonesia. Adapted from van Leeuwen, 2007.

Figure 4. Per capita GDP growth in Indonesia. Adapted from van Leeuwen, 2007.Of the four countries mentioned by Barro, Indonesia is the slowest to recover from the 1997 crisis. Barro rightly points out that an important factor in this is the current lack of foreign investment (Barro, 2001: 1). He comments that “the failure of investment to recover suggests that businesses do not anticipate returns to the sustained high growth of the past.” Thus, logically, the current investment climate is caused by sharply decreased confidence in the economy, which can also be seen in the stock market.

That the national economy is indeed ready for, and, to be more precise, deserving foreign investment is clear from the flexibility that has assured fast recovery from former economic slumps and from the process of structural reformation of “banking sectors (…), protection (…), state enterprises (…), taxation structures (…).” (Hill, 1994: 834). The Indonesian government tries to stimulate a more positive image of the Indonesian investment climate, mentioning very positive numbers:

“The rupiah has appreciated from a low of 17,000 to the dollar to a steady 8,500. The budget deficit has shrunk from 4.8% of GDP to 1.8%, and government debt from 100% to 67%. Inflation, which peaked at 60% in 1998, is down to 6% and still falling. Buoyed by this parade of encouraging figures, the stock market has recently hit several successive three-year highs.” (Economist, 27 Sept. 2003).

However, the Economist also points out some less positive trends(27 Sept. 2003). Politics are still highly unstable, and it is mainly the IMF, not the Indonesian government, that made the figures the latter is so proud of come into being. The IMF program has ended in 2004, and corruption and bureaucracy persist. “During Indonesia's rainy season, the dirt tracks that connect Javanese villages to their fields often become impassable. According to one estimate, every dollar spent surfacing these roads--with sand, rock and gravel--brings benefits worth $3.30 over the roads' lifetime. (…) Some of the World Bank money allocated to village infrastructure ends up greasing palms, not smoothing gravel.” (Economist, 18 March 2006).

Corruption and political instability are the main reasons for a lack of international confidence. However, corruption has a particular origin in Indonesia. According to King, there were corruption-like practices in the traditional tribal society, already in the 10th century. These were not illegal, but constituted a system of reward: the king could grant a good civilian a position in which the latter was expected to engage in self-enrichment (King, 2000: 605). Later, the Dutch used these mechanisms in the same way (King, 2000: 606). Corruption rose to current numbers under presidents Soekarno and Soeharto, as a consequence of his ignorance and personal benefit to maintain the status quo (King, 2000: 607-609). For many, there was no other way to urn a living. Furthermore, law-enforcement was hardly exercised with respect to corruption, allowing a climate of disregard of the law to emerge. King remarks that during the initial post-war growth, corruption declined profoundly, mainly because of the favorable economic climate, idealism, and effective law-enforcement (King, 2000: 606). Thus, on the long term, there is hope for foreign investors, provided that the government resumes enforcement of the law. However, their contribution is also necessary to establish, via economic growth, more favorable conditions for the people.

References:- Airries, C.A. “Global economy and port morphology in Belawan, Indonesia”. Geographical Review, Vol. 81, Issue 2, 1991.

- Antlov, Hans (Review author). [Kosuke Mizuno. “Rural Industrialization in Indonesia: A Case Study of Community-Based Weaving Industry in West Java”.] The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 56, No. 4 (November 1997), pp. 1172-1173.

- Barro, Robert J. “A 'YANKEE IMPERIALIST' OFFERS ASIA A ROAD MAP”. Business Week, Issue 3736, 2001.

- Britannica (Indonesia). Date of access: 18 September 2007. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-22814/Indonesia

- Countryprofile (Indonesia). Date of access: 18 September 2007. http://www.asianinfo.org/asianinfo/indonesia/pro-history.htm

- Geertz, Clifford. Agricultural Involution. The Process of Ecological Change in Indonesia. London: University of California Press, 1963. Fourth ed. 1970.

- Hill, Hal. “ASEAN Economic Development: An Analytical Survey--The State of the Field”. The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 53(3), 1994.

- King, Dwight Y. “Corruption in Indonesia: a Curable Cancer?” Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 53(2), 2000.

- Leeuwen, van, Bas. (2007). Human Capital and Economic Growth in India, Indonesia, and Japan: A quantitative analysis, 1890-2000. Doctoral thesis Utrecht University.

- Library of Congress Country Studies (Indonesia). Date of access: 18 September 2007. Contents page: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/idtoc.html . Quotation from: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field%28DOCID+id0021

- PBS (Pelabuhan Belawan statistik). 1985. Medan: Port of Belawan Statistics Department.

- UNDP (Indonesia). Date of access: 18 September 2007. http://www.undp.or.id/

- UN World unrbanization prospects, 2005. (Indonesia). Date of access: 18 September 2007. http://esa.un.org/unup/p2k0data.asp

[1] The resources listed by the CIA Factbook are: “petroleum, tin, natural gas, nickel, timber, bauxite, copper, fertile soils, coal, gold, silver” (CIA Factbook).

[2] Java was an interesting place for the company since it was already developed as a regional trade centre (Tichelman, 1980: 105). Infrastructural changes were, at first, hardly implemented, since these trade centres were located in the Pasisir (i.e. coastal) region of Java.

[3] The Cultivation System held that every village or settlement had to export the crops produced on one fifth of all its cultivatable land to Holland.

[4] There were conditions to prevent too rigorous exploitation. For example, Dutch entrepreneurs could only lease the land if that would not imply that the local inhabitants were enough denied resources to sustain their livelihood.

[5] As is quite usual when large scale violence occurs, there was no money or initiative to start building up an infrastructural network or invest in industrialization.