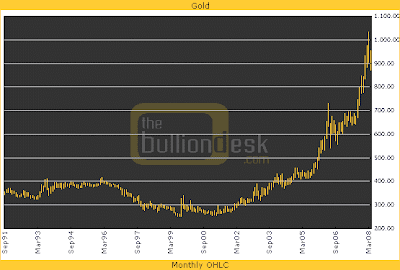

According to expectations, the gold price, having followed a continuous upward movement, has indeed surpassed the $1000 mark in February 2008. Credit crunch, stock market crash, and inflation have been enticing people all over the world to invest in gold. The press comments that gold has become the world’s most powerful currency. In contrast to paper currencies, gold cannot be arbitrarily augmented.

Figure 1: Gold price in Dollar

Source: The Bullion Desk (2008)

While bonds and certificates of deposit depend on the creditworthiness of the issuer, gold investments are unbound to payment promises of firms or governments. Possessing physical gold represents an insurance against a devaluation of both currency and assets. Notwithstanding, this does not mean that the gold price cannot fall. Speculators also get in on gold and can contribute to overheating and fierce adjustments (the current gold price is below 1000 dollar). The rising gold price is also linked to excessive borrowing arrangements. Due to the lax monetary policy of central banks the share of credits in US GDP rose from 150% in 1969 to currently 340%. At the same time, investors’ risk awareness kept decreasing, as they could incur additional debts or pay debts with new debts without difficulty. Things are difficult when the “monetary fuel” runs short and the borrower is unable to repay his debts.

Hitherto the gold price often used to increase rapidly during phases of low or negative real rates (Fed fund real rates), i.e. whenever the inflation rate considerably exceeded interest rates (so that depositors could not make gains on their assets). In that case, the main disadvantages of gold investments, i.e. that one cannot earn interests or dividends, do not matter. Not only the fear of inflation but also the rising demand from newly industrialising countries inflates the gold price. More and more people from those countries can afford jewellery and gold bars. Accordingly, China’s demand has increased to nearly 300 tons per year since the gold market liberation in 2002 (private property and ownership of gold were forbidden before). With a demand of more than 700 tons per year India has the world’s largest gold market. Indian wives regard gold property as a form of life insurance and old-age provisions, while in the Western world gold is still regarded as something exotic.

Most of the gold is processed in the adornment industry. According to GFMS, jewellers processed 2407 tons of gold in 2007, which was 63% of the worldwide gold supply. The remainder dispersed among the industry, dental technicians, gold investors, and gold mines. Despite the rising gold price the worldwide gold mining remains stagnant. This can be explained by the ongoing increases in costs of material, energy, and logistics with respect to gold mining and the scarcity of new sources with high gold content. Moreover, there are hindrances such as institutional problems and time: The phase from gold discovery to commercial production takes at least seven years. Besides, projects drag on because of interminable licensing procedures and environmental protection amendments. Also, gold producers shrink away from investing in regions of political instability due to lacking legal security. Finally, investment opportunities deteriorated in light of the credit crunch and stock market crisis.

People who would like to purchase gold assets are advised to choose services offered by internationally famous and acknowledged bullion dealers. The prices of their products almost move together with the gold value. People who want to stock their bars and coins in bank safes should acquire sufficient information on insurance coverage; those who prefer to stock at home ought to make sure that the household insurance is adjusted. Also the home safe has to meet standards as required by the insurance. Alternatively, banks offer investments in gold (price) certificates, which are free of storage or insurance expenses. Moreover, they are more tradable compared to physical gold. However, gold certificates are bearer debentures and thus are receivables against the issuer. If the issuer’s credit standing deteriorates or if he becomes insolvent, the certificate owner also runs the risk of losing his stakes or parts of them.

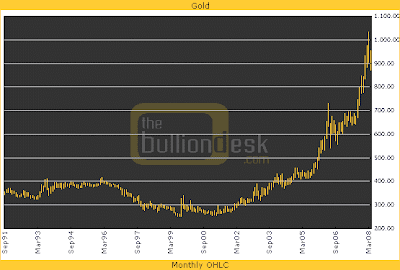

Contrary to investment funds or Exchange Traded Funds (ETF), certificates do not represent separate assets which are protected in bankruptcy cases. An alternative to certificates are ETFs which purchase gold with investors’ money; the gold bars are then kept by a fiduciary. Investors who are only aimed at short-run gold price movements are not recommended to gamble with gold bars. Although the demand for gold has been increasing, the proportion of gold in investors’ portfolios is still very low, despite the fact that gold has been performing better than stocks for years, something that is expected to remain also for the next few years, according to the Dow-gold ratio. This ratio is calculated by dividing the average Dow Jones index level of a period by the gold price in US dollar of the same period. A decreasing ratio means that gold performs better than US stocks and vice versa. Even if this concept does not say much about the absolute price development, it proved to be a fairly good long-run indicator.

Figure 2: Dow-gold ratio

Source: www.chartoftheday.com (2008)

Central banks and IMF held 29955 tons of gold at the end of 2007, with a market value of 890 billion dollar. This gold largely stems from times when the issuance of paper-money had to be backed by gold. It is actually unknown which of this gold are still in the safes of central banks or has been already sold to the market. The USA possesses the largest hoard of gold with 8134 tons, followed by Germany (3417 tons) and IMF (3217 tons), but they strictly reject sales of gold so far. Theoretically, central banks and IMF are capable of flooding the gold market and, in this way, beating down the gold price which represents a crisis indicator to them.

Links and References:

- Doll, F. (February 18, 2008). Omas olle Klunker. Wirtschaftswoche, pp.126-137